Ever wondered how to figure out what a bank is really worth? And not in the textbook (technically true, but practically useless) case?

Well, buckle up, because we're about to dive into the world of bank valuation. I’m going to try to give you a way to “value” (which really means price in most cases) a bank as well as what you need to think about when you make investment decisions in the bank space.

Appropriate given the breakout in financials and banks lately.

The Bedrock: Tangible Book Value (TBV)

Jamie Dimon once said, "If our asset and liability values are appropriate—and we believe they are—and if we can continue to deploy this capital profitably, we now think that it can earn approximately 17% return on tangible equity for the foreseeable future. Then, in our view, our company should ultimately be worth considerably more than tangible book value"

In essence, Dimon was emphasizing the importance of accurately valuing a company's assets and liabilities. If these values are correct, the tangible book value (TBV) becomes a reliable measure of the company's worth. TBV represents the net asset value of a company, excluding intangible assets like goodwill. When a company can deploy its capital profitably, it can generate returns that exceed its TBV, indicating strong financial health and potential for growth.

Tangible Book Value is like the bank's bare-bones net worth. It's what would be left if you sold all the bank's stuff and paid off all its debts.

To calculate TBV:

Start with total shareholder equity - this represents the net assets of a company, which is the difference between total assets and total liabilities. It includes both tangible and intangible assets, such as goodwill and intellectual property.

Subtract intangible assets (things like goodwill, brand value, and intellectual property). Historically, banks haven't been known for having significant brand value or intellectual property (IP) compared to other industries like technology or consumer goods. Goodwill is an intangible asset that arises when one company acquires another for a price higher than the fair market value of its identifiable assets and liabilities. It represents the value of a company's brand name, customer relationships, employee relations, and other factors that contribute to the company's reputation and profitability. Essentially, goodwill reflects the premium a buyer is willing to pay for the acquired company's potential to generate future earnings beyond the value of its tangible assets.

Subtract preferred equity (if any). Preferred shares sit between debt and equity in the capital stack. Their holders get paid dividends before common equity, but they do not have voting rights. Why do banks issue these? Primarily they help banks meet capital requirements, they count towards Tier 1 (a major regulatory benchmark) so long as they meet certain criteria. And more importantly banks issue these because they are typically much cheaper than issuing common. Issuing common shares gives people a slice of the business returns forever (which can be north of 10% or higher) whereas preferreds issue only a fixed coupon typically in the high single digits.

What's left is TBV. And in JPM 0.00%↑ case they’ve grown TBVPS from around $12 to $95 over the past 24 years for a roughly 8% CAGR. This is best in class.

Market Value & “The Multiple”:

Here's where it gets interesting. When you look at publicly traded banks, you'll often see them trading at a premium or discount to their TBV. It's like the market is saying, "Hey, this bank is worth more (or less) than the sum of its parts." This is called a multiple and there is some wisdom in this multiple if you know what you’re looking for. Are you paying a fair price for a wonderful business? Or a high price for an average business?

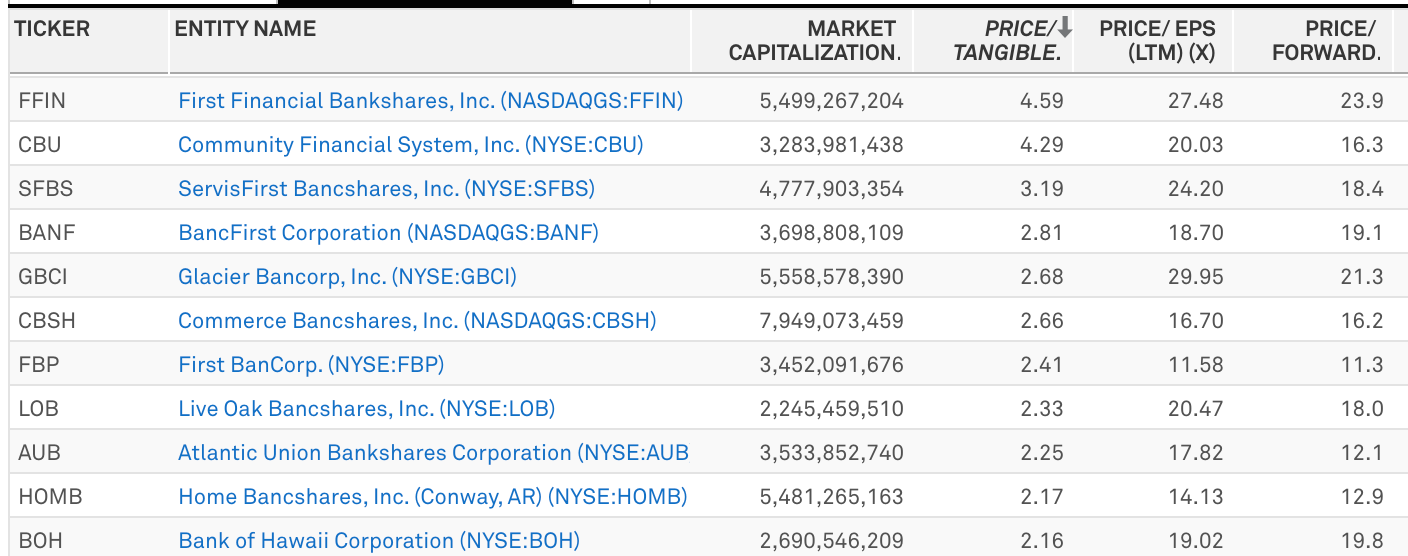

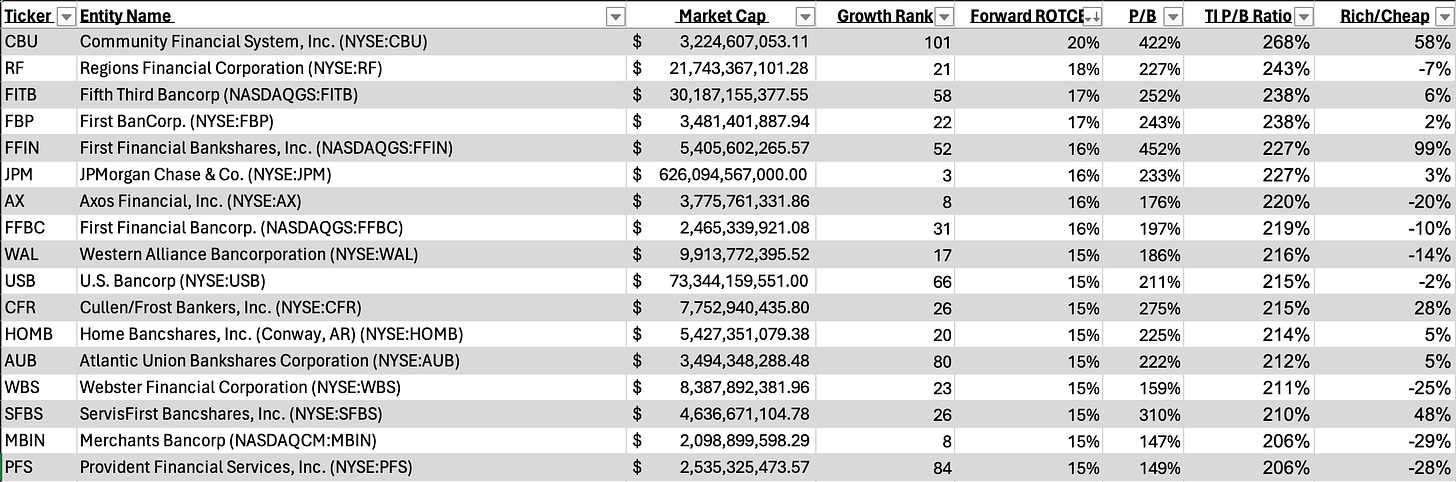

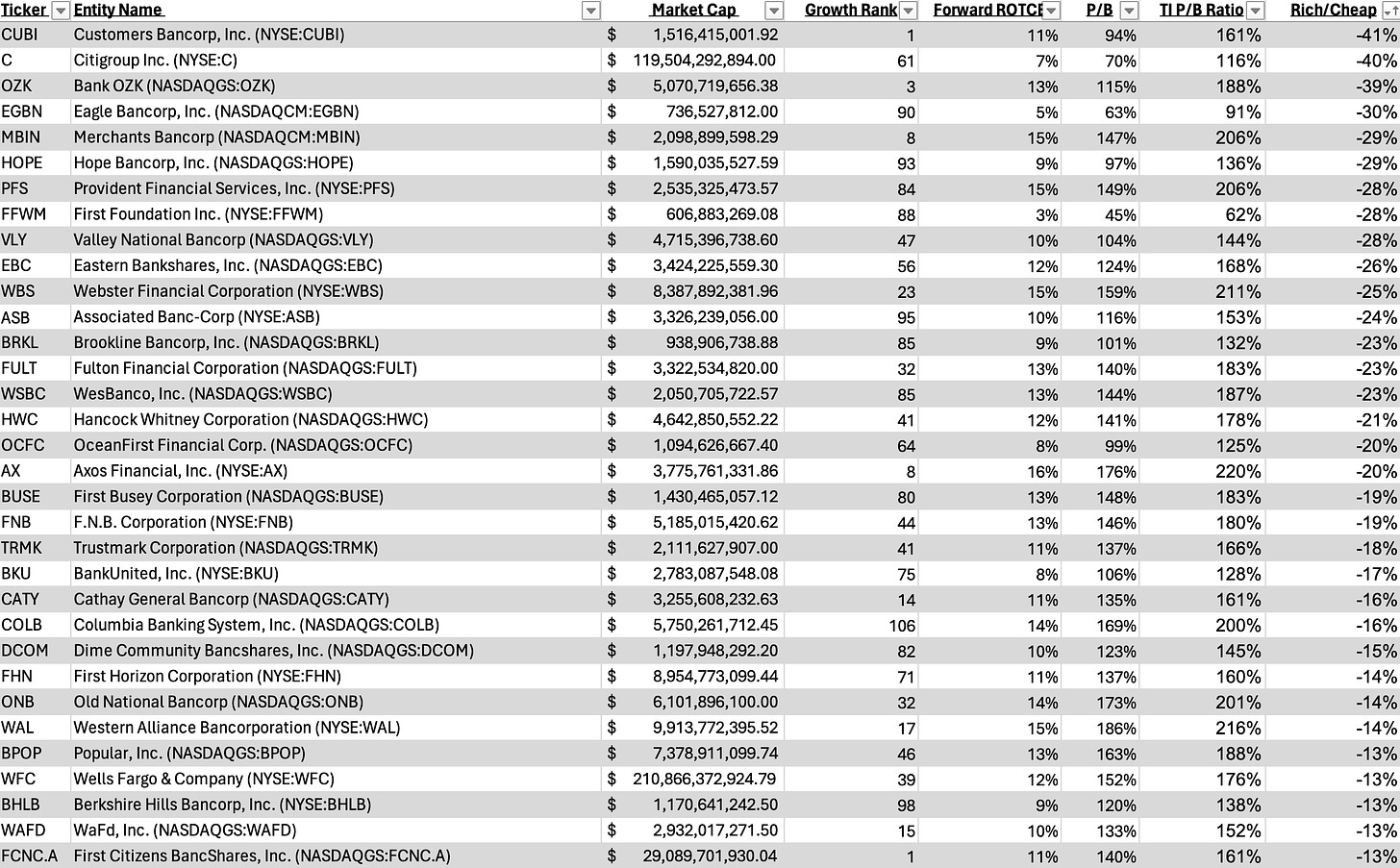

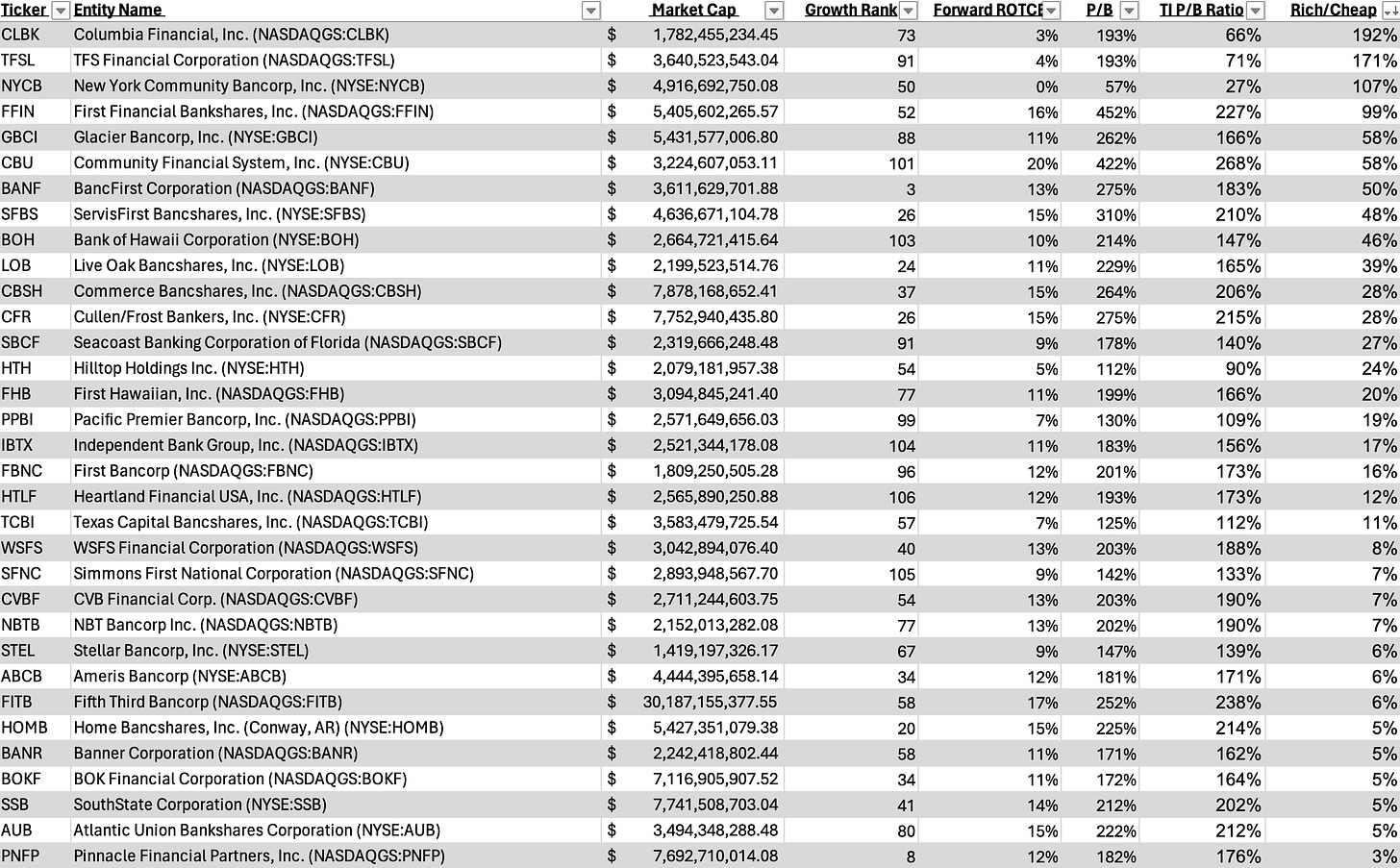

Here are a few expensive regionals based on P/TBV:

And here are a few cheap regionals based on P/TBV:

A discount multiple means investors think you are “worth less” (not worthless) than the market. They probably think your go forward returns are below your cost of equity capital (more on this later). This usually happens when investors are worried about the quality of the bank's assets or its ability to generate profits in the future. Again, these companies are typically associated with lower than market returns on tangible common equity and a track record of futility.

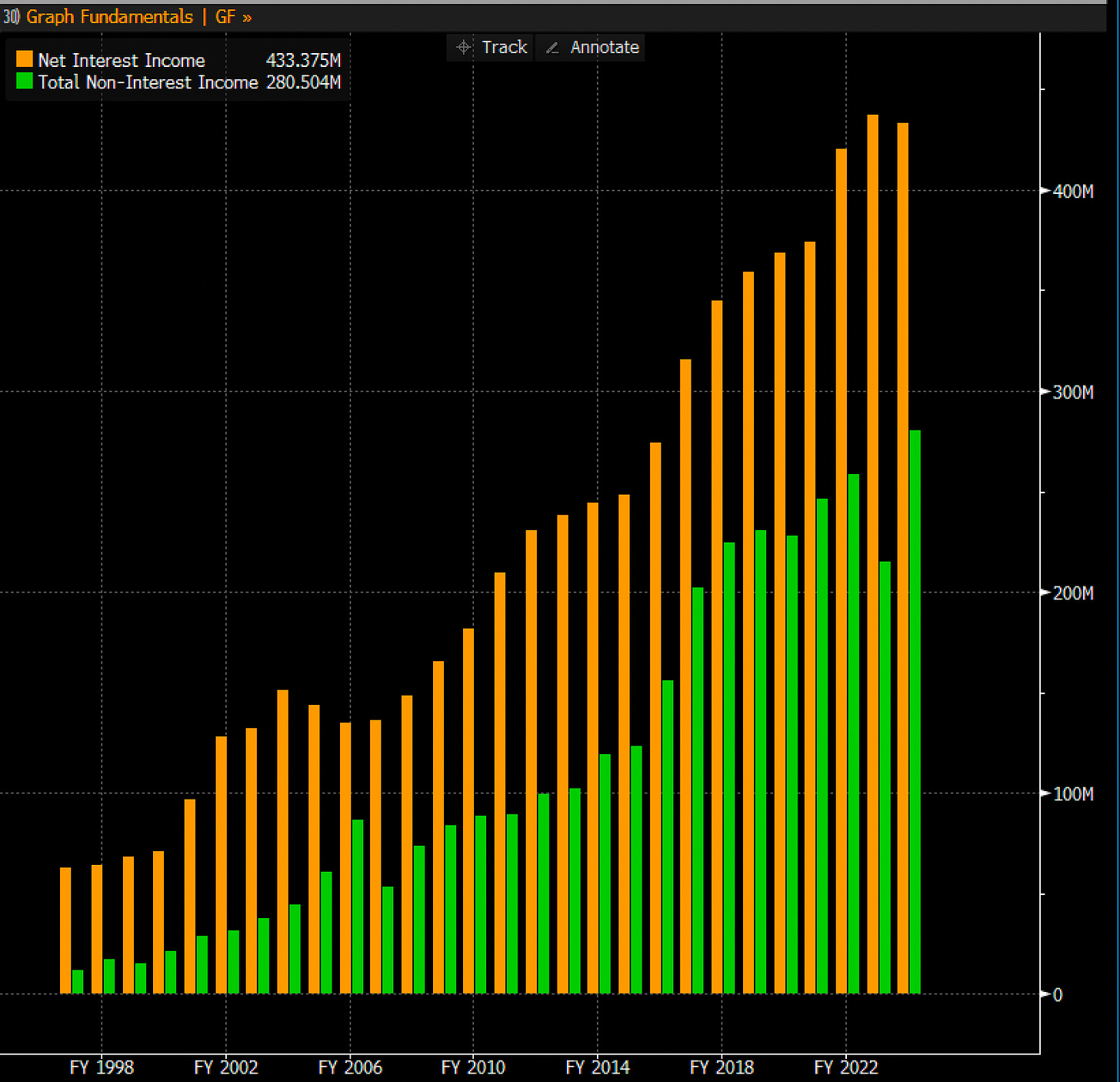

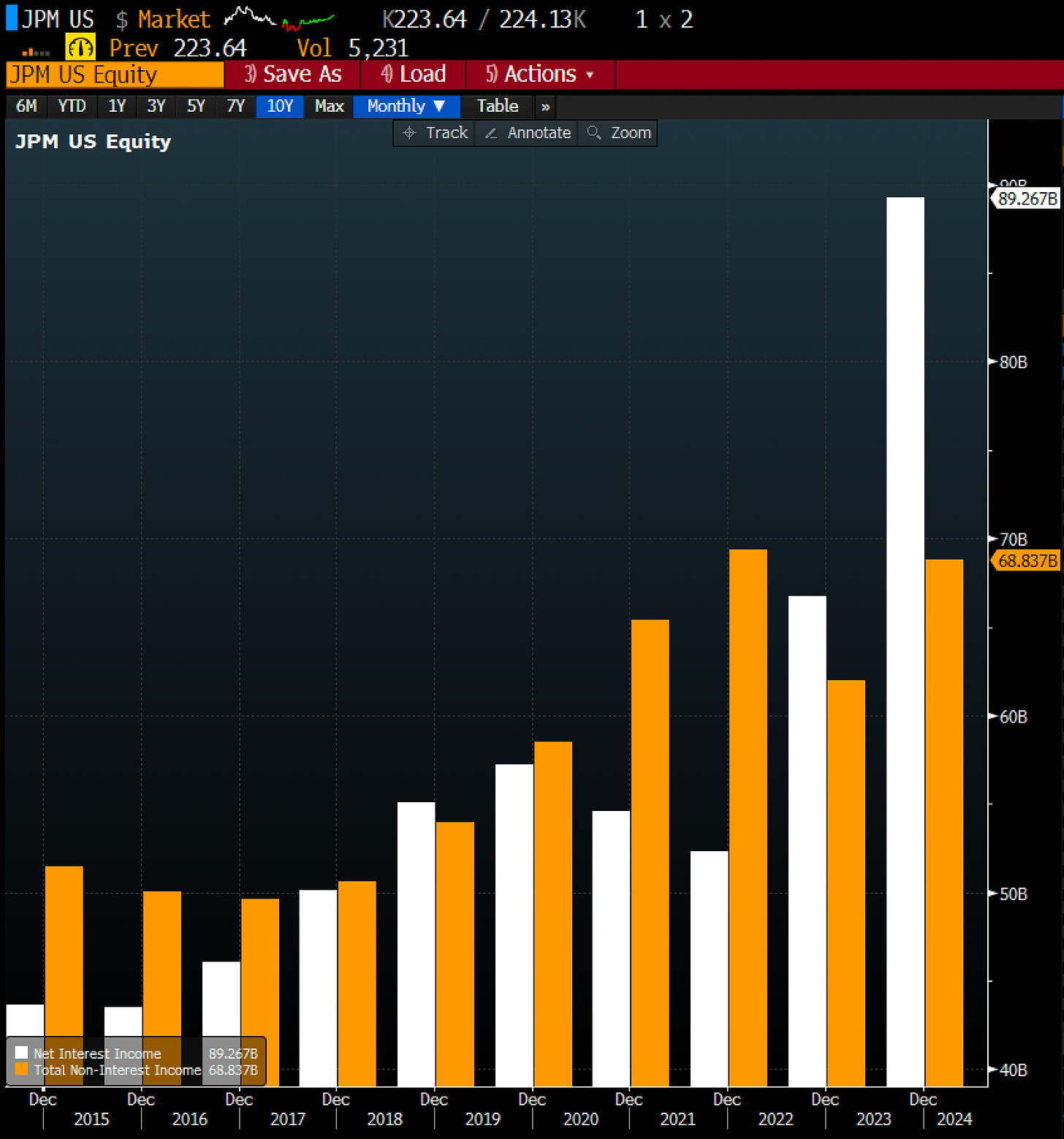

So, what does a premium multiple mean? That means investors think JPMorgan's franchise, its ability to generate future profits, and its management are worth a lot more than just its net assets. Typically, these companies are associated with above market returns on tangible common equity and more than likely a track record of doing so over a period of time. A premium multiple in banks could also mean (like in CBUs case) more income derived by non-bank multiple businesses along with high returns. This is CBU 0.00%↑ and their net interest income and non-interest income over time, I’ve never seen such a beautiful thing for a “community” bank. Constant growth. You kind of don’t need to listen to management’s words when their actions are this consistent.

In another “expensive” bank’s case FFIN 0.00%↑ it has an unbelievably long track record of growing EPS & TBVPS for investors. Long track records mean trust. Trust means multiple. Another “thing of beauty” chart is their EPS & TBVPS going back to the early 1990’s. Up until recently it only went up and to the right. Both have CAGR (compound annual growth rate) at just north of 8% a year for (checks notes) 34 years as a public company.

So how does someone “value” a bank?

Picture this: You're on the bank version of Pawn Stars, rolling up to Vegas with your prized bank stock. You stroll in, ready to ask Chum Lee if he wants to buy your bank. But before you hear him say, "Do you wanna pawn it, sell it, or donate it?"—do you even know what it's worth? Time to find out if your stock is a hidden gem or just another dusty relic!

The Big Three: Valuation Methods

Next, let's talk about how the suits on Wall Street value banks. They've got three main tricks up the sleeves of their $5000 suits.

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF)

Comparable Company Analysis

Precedent Transactions

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF): The Crystal Ball Method

DCF is kind of the nerd version of the gold standard but is like trying to predict the future. You estimate all the cash the bank will make in the coming years, then figure out what that's worth today via present value. Sounds simple, but it’s not.

And among other things, the key ingredient here is the discount rate, often calculated using the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). It's supposed to represent the return investors demand for taking on the risk of owning the bank's stock.

The CAPM formula looks like this: Expected Return = Risk-Free Rate + Beta * (Market Return - Risk-Free Rate)

Where:

Risk-Free Rate is typically the yield on government bonds

Beta measures how much the stock moves compared to the overall market

Market Return is the expected return of the overall stock market

And remember, high discount rates always decrease the value of future cash flows, while low discount rates always increase the value of future cash flows.

Aswath Damodaran, the "Dean of Valuation," has some choice words about DCF:

"A good valuation is a bridge between stories and numbers."

He emphasizes that while DCF can be powerful, it's only as good as the assumptions you feed into it. Garbage in, garbage out, as they say.

Damodaran suggests some best practices for DCF:

Use cash flows, not earnings (for banks this is net income)

Be consistent with growth rates and reinvestment

Don't mix accounting and cash flow numbers

Be careful with terminal values (they often make up a large portion of the valuation)

And here's the rub with banks: their cash flows are... weird. Unlike a regular company that makes widgets, a bank's cash flows are tied up in loans, deposits, and financial instruments.

CFA types may try to force you to use a DCF when valuing banks, but for me it’s not practical. Yes, you can build a model, but it’s burdensome and almost always wrong, especially if you don’t know what you’re doing.

And you can use net income when valuing bank cash flows, but it's not the only metric to consider. Net income provides a snapshot of a bank's profitability, but it doesn't capture the full picture of cash flows. For a more comprehensive valuation, you could consider metrics like Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE) or the Dividend Discount Model (DDM), which are better suited for financial institutions. These models take into account the unique capital structure and regulatory environment of banks, providing a more accurate assessment of their value.

This is the technically true, but practically useless. You’re not going to be able to run this when you want to invest in a bank either.

Comparable Company Analysis: The "Keeping Up with the Joneses" Approach

This method is all about looking at similar banks and seeing how the market values (prices) them. The two big metrics here are Price-to-Tangible Book Value (P/TBV) and Price-to-Earnings (P/E).

P/TBV tells you how much investors are willing to pay for each dollar of a bank's tangible book value. A P/TBV above 1 means the market thinks the bank is worth more than its net tangible assets. A P/TBV below 1 means the market thinks the bank is worth less than its net tangible assets.

P/E, on the other hand, tells you how much investors are willing to pay for each dollar of the bank's earnings. A higher P/E could mean investors expect higher growth in the future, or it could mean the stock is overvalued.

Michael Mauboussin, a valuation guru, has some interesting thoughts on P/E ratios:

"P/E multiples are not valuation tools; they are shorthand for the valuation process."

In other words, a P/E ratio is like a shortcut. It can give you a quick and dirty estimate, but it doesn't tell the whole story.

Mauboussin also points out that steady-state P/E ratios are closely tied to the cost of capital. The lower the cost of capital, the higher the justified P/E ratio. He provides a simple formula:

Steady-state P/E = 1 / (cost of equity - growth rate)

This formula shows why low interest rates can lead to higher P/E ratios: they lower the cost of equity, pushing P/E ratios up.

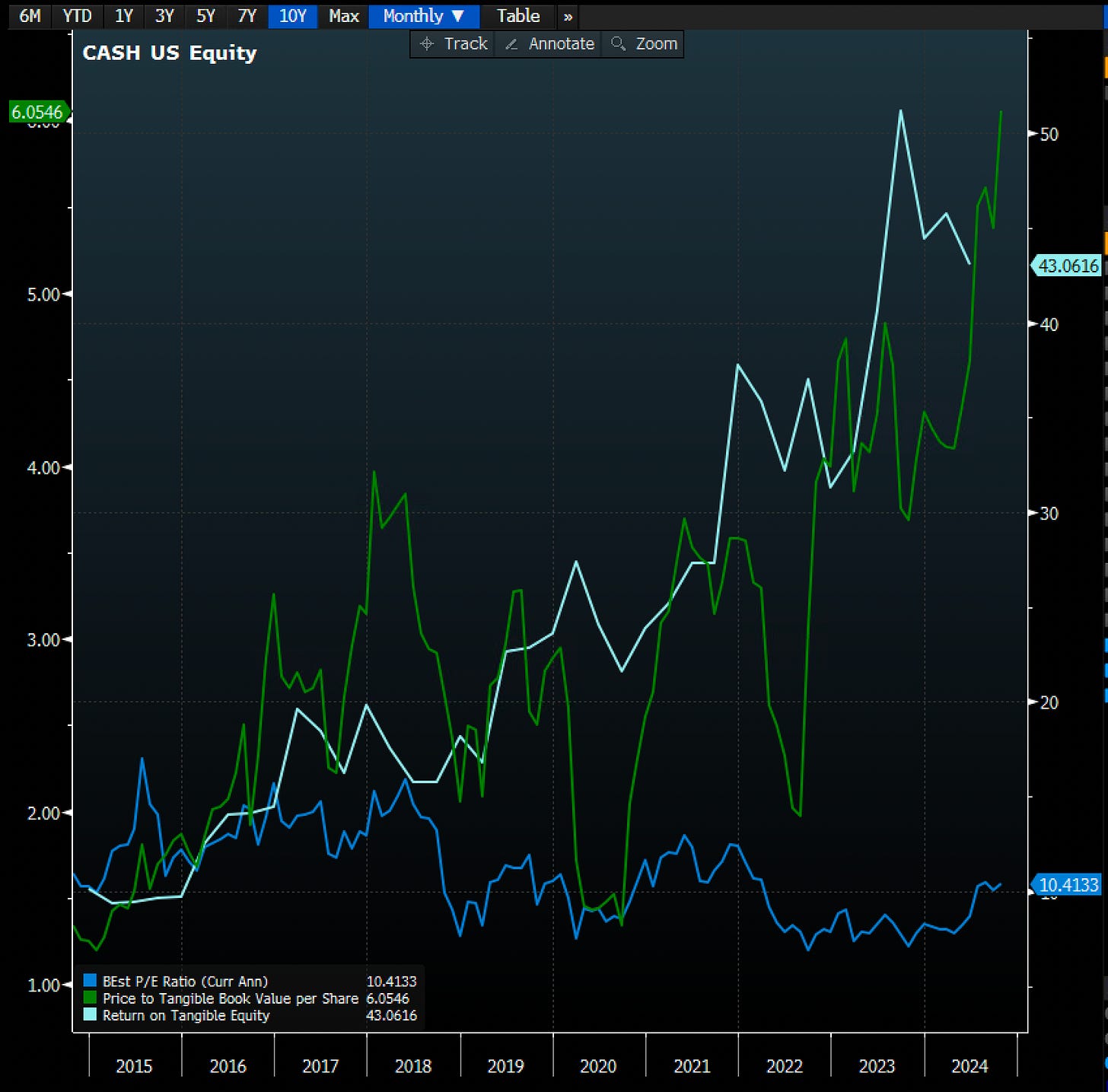

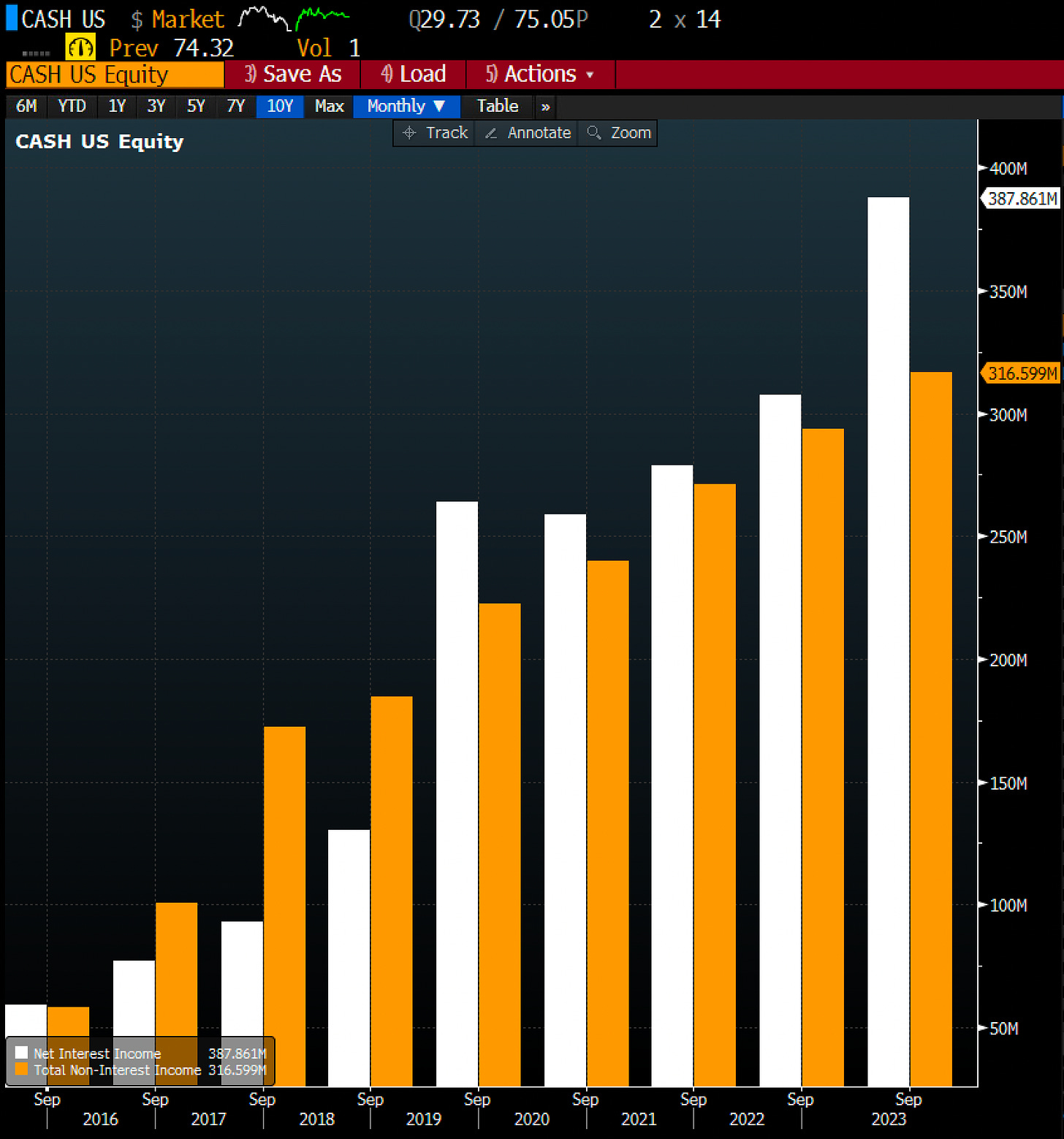

Mauboussin explains also that a company can justify a higher P/E multiple if it consistently earns returns above its cost of equity. This is because the company is effectively generating value for its shareholders. When a company's return on equity exceeds its cost of equity, it indicates that the company is using its capital efficiently to generate profits. Investors are willing to pay a premium for such companies, resulting in a higher P/E multiple. CASH 0.00%↑ is a great example of this phenomenon in the banking space. And below is I think every chart crime known to humankind, but it illustrates the point well. The bank is a Fintech/BaaS bank which makes its money very differently than most “community banks”. It trades at an astoundingly high P/TBV (Bloomberg is not perfect at this metric) but a reasonable forward P/E multiple at around 11x forwards. Both things being justified by their big ROTCEs.

And with P/E, the inverse of the P/E ratio is often used as a shorthand for the cost of equity. This inverse is known as the earnings yield, which is calculated as Earnings per Share (EPS) divided by the stock price. The earnings yield provides an estimate of the return an investor can expect to earn from the company's earnings relative to its stock price.

I personally have flippantly (and incorrectly) used this earnings yield as a proxy for the cost of capital. And like many things in life, you shouldn’t model all of your behavior after mine, but I digress. For example, the “cost” of equity for a company like AAPL is something like 2.8% given its 35x P/E multiple, whereas JPMs “cost” of equity is something like 8% given its 12x P/E multiple. Again, not perfect but you should get the point. For banks overall right now via KRX (Regional Bank Index) the “cost” of equity is also around 8% given its trading around a 12x P/E multiple. If a Company within banking is set to earn north of 8%-10% it should have a slight premium multiple.

Deeper analysis of cost of equity will likely take you to a deep dark place you don’t want to go, so I tend to leave it at this, know roughly what it is and move on.

But there’s a catch with using multiples for banks: they can be as misleading as a politician's promise. Banks can juice their earnings through aggressive lending or accounting tricks, making their P/E look artificially low.

When using comparable company analysis for banks, it's crucial to consider factors like:

Asset quality - how are NPLs? how are NCOs? do they do non-recourse CBD office? do they do low LTV resi? and so on.

Loan portfolio composition - are they concentrated in one industry or one geography and so are they over levered to a binary outcome? TFIN not to pick on, but only to note with respect to trucking comes to mind.

Funding mix - do they rely on short CDs like most thrifts in the country? or do they have a bunch of low-cost business checking accounts?

Regulatory environment - are their CET1 or concentrations causing regulatory scrutiny?

These factors can explain why seemingly similar banks might trade at different multiples. And they should.

Returns on TCE and Market Multiple?

I mentioned this earlier, but the relationship between Price-to-Tangible Book Value (P/TBV) and Return on Tangible Common Equity (ROTCE) is quite significant. Generally, banks with higher ROTCE tend to have higher P/TBV ratios. This is because ROTCE is a measure of a bank's profitability, and higher profitability often leads to higher valuations. Investors are willing to pay a premium for banks that generate strong returns on their tangible equity, which drives up the P/TBV ratio.

In fact, studies have shown a positive correlation between ROTCE and P/TBV, indicating that as ROTCE increases, so does the P/TBV multiple. This relationship underscores the importance of profitability in determining a bank's valuation.

So, when evaluating banks, it's crucial to consider both ROTCE and P/TBV to get a comprehensive understanding of their financial health and market valuation.

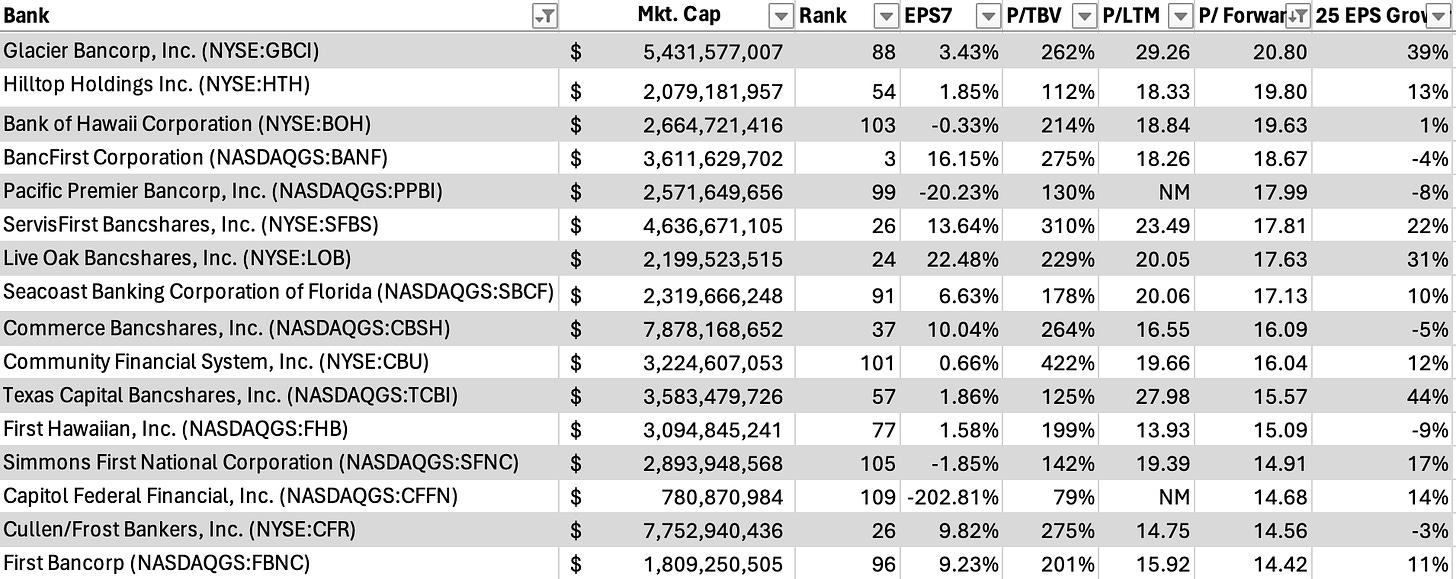

I run these screens regularly to see the relationship between the two different variables. This below is for all public banks above $10 billion in assets. What do you notice? I see a correlation (not causation).

They also shed light on the why behind a name trading cheap or expensive to trend. A quick look shows you that a bank like WBS 0.00%↑ or PFS 0.00%↑ trades “cheap to their otherwise implied ROTCE valuation because they have a lot of CRE (among other things). So given uncertainty around future commercial real estate credit, investors will discount valuations. You also have banks like FFIN 0.00%↑ which sports a mega premium valuation, but this is in large part to the fact that they are unbelievably consistent at pumping out returns.

Growing Earnings and Market Multiple?

Investors are willing to pay a higher Price-to-Earnings (P/E) ratio for banks that consistently grow earnings because it signals strong future growth potential and financial stability. When a bank demonstrates consistent earnings growth, it indicates that the bank is effectively managing its operations, expanding its market presence, and generating higher profits. This instills confidence in investors that the bank will continue to perform well in the future.

Higher earnings growth also means that the bank can reinvest profits into new opportunities, pay dividends, or buy back shares, all of which can enhance shareholder value. As a result, investors are willing to pay a premium for such banks, reflected in a higher P/E ratio.

You can look at a bank like LOB 0.00%↑ who historically has been able to grow EPS above and beyond their peers (you’re looking at a trailing 7-year CAGR) which gets them a premium multiple. Banks like BANF 0.00%↑ are another example of long-term track records of growing EPS, which people reward with a higher multiple.

Precedent Transactions: The "What Have Others Paid?" Method

This one's simple: look at what other banks have sold for in the past. It’s also the least useful for me. And that’s because every bank is unique. Just like Forrest Gump said, “life is like a box of chocolates, you never know what you’re going to get” the same is true of banks. Finding a “true” precedent is pretty tough.

When looking at precedent transactions, pay attention to:

The premium paid over the target bank's stock price

The P/TBV and P/E multiples of the deal

The strategic rationale behind the acquisition

The economic and regulatory environment at the time of the deal

For example, in 2022, TD Bank announced its acquisition of First Horizon for $13.4 billion, representing a 37% premium to First Horizon's closing share price. The deal valued First Horizon at about 2.1x its tangible book value. But here's the kicker: in May 2023, TD Bank called off the deal due to regulatory concerns. So, this ended up not being a “good precedent” and this is mostly because it would later be found out that TD was doing some awful and shady stuff with unsavory characters. This landed them in purgatory with the regulators as it should.

More examples can be found in a friends X account: Follow Rick Childs. At current of all announced 2024 bank M&A deals they’ve carried around a 125% to 135% P/TBV multiple. Credit unions have paid way above these for the most part which is distorting “true value” for banks, in my opinion. The fact that they’re not taxed, don’t pay dividends, and have different goodwill accounting means they can drastically overpay.

But with comparable transactions you’re probably going to get to some level of the same place that you would with my ROTCE / P/TBV scatter framework plus or minus a little. So, I tend not to use it. Beware: investment bankers and real estate agents love using this one to drive up prices in M&A.

The Nitty-Gritty: Bank Earnings Cash Flow Drivers

Here are some of the main things that drive Net Income for a bank. I care primarily about net income and EPS because I believe that over the long-haul earnings via EPS and bank value are correlated. That plus Revenue per Share and Tangible Book Value per Share all contribute to growing shareholder value.

For Bank Net Income/Earnings/EPS here are the main levers:

Net Interest Income: This is the spread between what the bank earns on loans and pays on deposits. For most banks (non-money centers) it’s typically 80% plus of the net income the bank generates. It's affected by:

Asset yields: The interest rates the bank charges on loans

Deposit costs: The interest rates the bank pays on deposits

Loan growth or contraction: How much the bank's loan book is expanding or shrinking

Paydowns of past assets & Repricings: How much the bank’s assets are coming back to them to be re-invested.

Mix Shift: On the same line, is a bank taking money from loans and putting it into lower yielding bonds, or vice versa.

Net Interest Margin (NIM) is a key metric here. It's calculated as: NIM = (Interest Income - Interest Expense) / Average Earning Assets

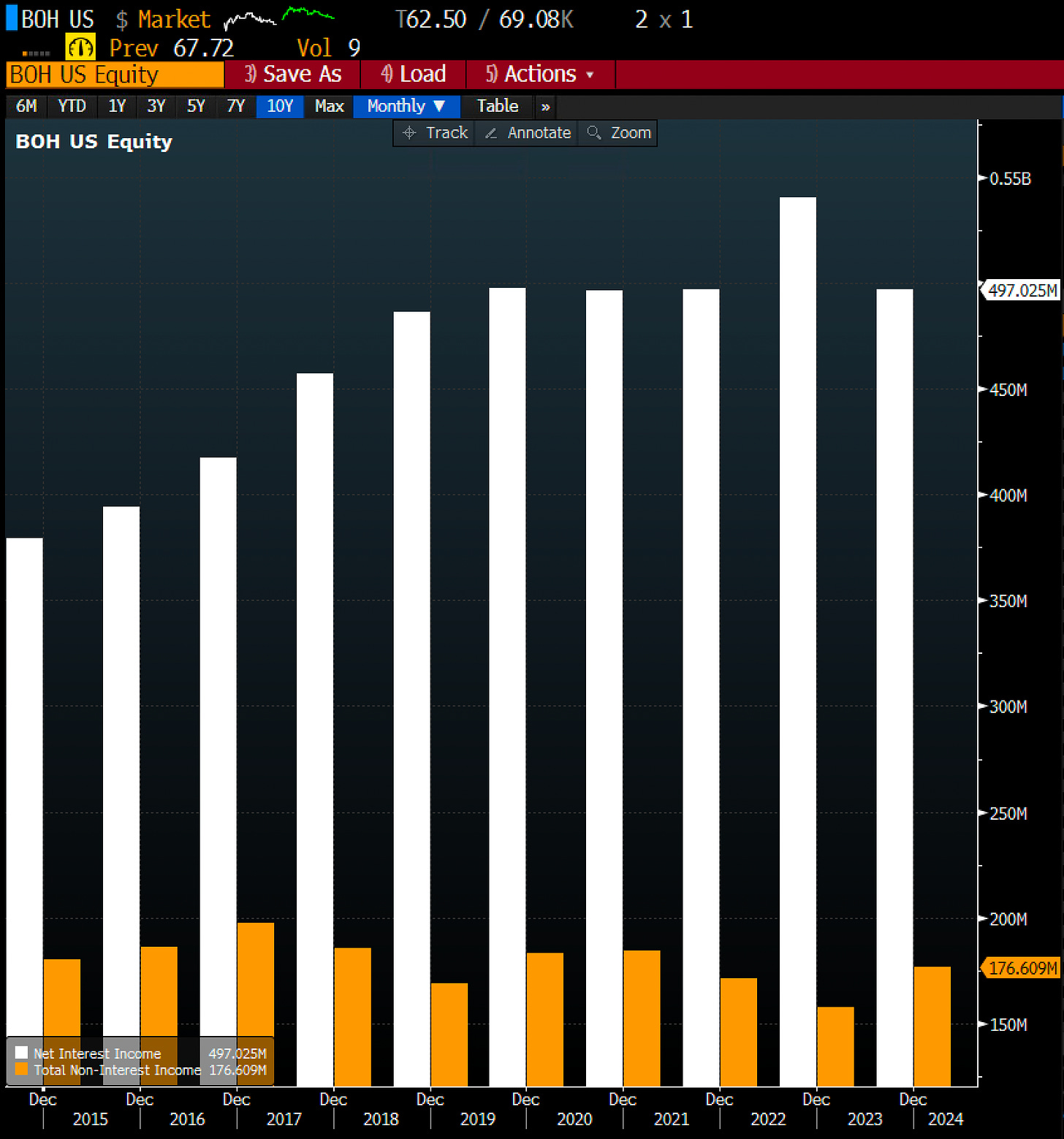

Banks that are overly dependent on NIM rarely carry a premium multiple to the rest of their cohorts. Unless of course they have a “moat” or “niche” lending vertical that no one else can touch.

Non-Interest Income: This includes fees from various services like:

Wealth management - Banks charge fees for managing investment portfolios and providing financial advice.

Investment banking - Banks earn fees from underwriting securities, advising on mergers and acquisitions, and trading.

Card processing - Banks make money from interchange fees, cardholder fees, and partnerships with card networks.

Mortgage banking - Banks earn through origination fees, interest on loans, and servicing fees.

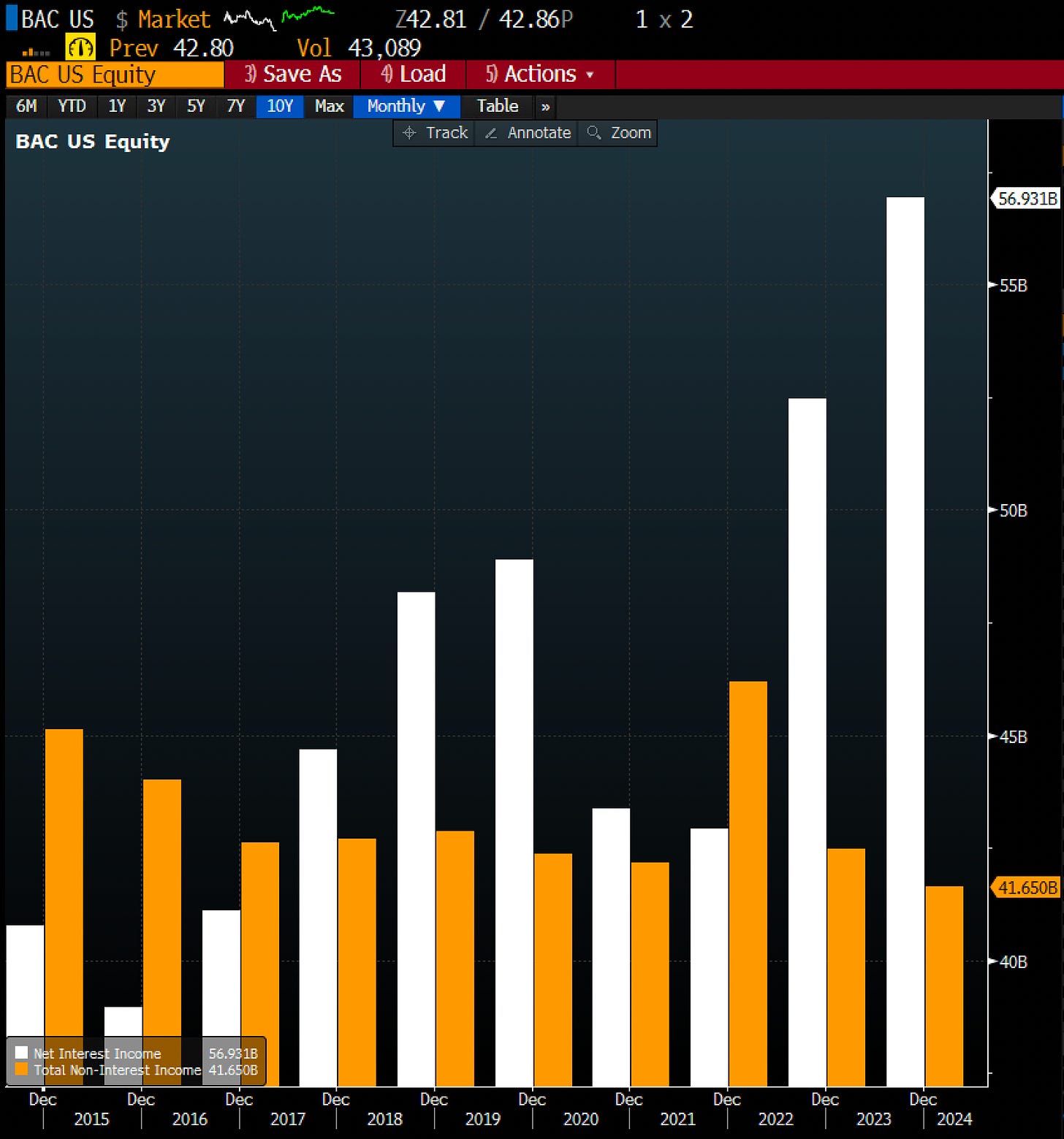

Each of these verticals can have a significant impact on the bank's overall value. For some banks, like Goldman Sachs, non-interest income can be a major part of their business. Banks with heavy non-interest income verticals with moats are the holy grail from a valuation standpoint and should trade higher. They’ve found a way to “escape” the low multiples present for most banks.

Non-Interest Expense: The majority of non-interest expenses for banks typically include personnel costs, such as salaries, bonuses, and benefits for employees. Information technology costs, which cover expenses related to maintaining and upgrading IT systems, also make up a significant portion. Additionally, legal and consulting fees, facility costs like rent, utilities, and maintenance, and marketing and advertising expenses are essential for the day-to-day operations of a bank. M&A works in large part because salaries of execs are a big number and when a merger happens you don’t need 2 CEOs or 2 CFOs (unless you’re EGBN).

Provisions for Credit: Provisions for credit at banks are funds set aside to cover potential losses from loans and credit exposures. These provisions act as a financial buffer, ensuring the bank can absorb losses from delinquent or defaulted loans. Essentially, it's a way for banks to prepare for and manage credit risk, maintaining financial stability and compliance with regulatory requirements

Asset Quality: This refers to the risk level of a bank's assets, particularly its loan portfolio. Key metrics include Non-Performing Loan (NPL) ratio, Net Charge-Off (NCO) ratio, Loan Loss Reserve ratio. Suffice to say you do want lower levels of these numbers. Credit is almost always what takes banks down and is why banks trade as levered beta (aka Cyclicals). Rising and falling with the broader health of the economy.

These other two aren’t directly EPS or Income related but do matter for valuations.

Capital Adequacy: Banks need to maintain certain capital ratios to satisfy regulators. The Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio is a key measure: CET1 Ratio = Common Equity Tier 1 Capital / Risk-Weighted Assets. A higher CET1 ratio means the bank has a stronger capital position, but it might also mean lower returns on equity. You want to shoot for being like JPM with a high CET1 and high returns (duh).

The Regulatory Landscape: A Necessary Evil: We can't talk about bank valuation without mentioning regulation. Since the 2008 financial crisis, banks have been subject to increasingly stringent regulations. These include Basel III capital requirements, annual stress tests for large banks, the Volcker Rule, which restricts proprietary trading. While these regulations have made banks safer, they've also impacted profitability. This regulatory burden is one reason why many banks trade at lower multiples than they did pre-2008.

Summarizing: Numbers 1 and 2 drive the ship. Number 3 matters. Numbers 4 & 5 matter eventually. To show this, look at these different banks. How they make money is drastically different and so their valuation will differ as well.

Bank of Hawaii breakdown of net interest income and non:

Bank of America breakdown of net interest income and non.

JP Morgan breakdown of net interest income and non.

Pathward Financial net interest income and non.

Now, let's put this all together. A bank's value is essentially a function of:

Its current tangible book value (TBV)

Its current earnings power (net income/EPS)

Its ability to grow those earnings

The quality and stability of those earnings

People’s perceptions of future earnings (P/E multiple)

As Simple as Possible and No Simpler:

Here is how I would value (price banks) if I were a novice or myself:

What's the bank earning now? Net income.

What will it earn in the future? Stick to 12 months and no further. Everything beyond that is fugazi.

What's that future earnings stream worth in terms of multiple? Is it more durable than others? Less durable? Adjust multiple based on the answers to those questions.

This should spit out some number. A $1 billion bank with $100mm of TBV making $10mm a year should be worth TBV plus some (25% is current premium for a decent bank). So, call it $125mm. If you see earnings as risky, it should be worth less. If you see earnings growth, it should be worth more.

From a macro standpoint you also have to have somewhat of an opinion/view on:

The interest rate environment (tailwind or headwind)

The stage of the credit cycle (kryptonite for the sector)

Potential regulatory changes (wet blankets on returns)

Investors love or hate for the sector (flows for pros)

Answer if you see things getting much better, much worse, or staying the same.

The Importance of Net Income and Future Earnings

A critical aspect of bank valuation is understanding a bank's net income - both current and projected:

1. Current Earnings Power: A bank's current net income provides a snapshot of its ability to generate profits in the present environment.

2. Future Earnings Potential: Projecting future net income is key to understanding a bank's growth trajectory and long-term value.

3. Earnings Quality: Not all earnings are created equal. Understanding the sources and sustainability of a bank's net income is crucial for accurate valuation.

Remember: Focus on the next 12 months of earnings. Anything beyond that becomes increasingly speculative.

Closing Thoughts: The Art and Science of Bank Valuation

As we conclude our exploration of bank valuation, let's recap the key takeaways and synthesize the critical concepts:

1. Foundation: Tangible Book Value (TBV) serves as the bedrock of bank valuation, providing a baseline for a bank's worth.

2. Valuation Methods: The three primary methods - Discounted Cash Flow (DCF), Comparable Company Analysis, and Precedent Transactions - each offer unique insights, but none are perfect on their own.

3. Key Drivers: Understanding the core drivers of bank earnings - Net Interest Income, Non-Interest Income, Non-Interest Expense, and Provisions for Credit - is crucial for accurate valuation.

Practical Valuation Tips

When valuing a bank, keep these practical tips in mind:

1. Start with the Basics: What's the bank earning now? What will it earn in the future (focusing on the next 12 months)?

2. Assess Earnings Quality: Is the earnings stream more or less durable than peers? Adjust your valuation multiple accordingly.

3. Consider the Macro Environment: Factor in the interest rate environment, the stage of the credit cycle, potential regulatory changes, and investor sentiment towards the banking sector.

4. Use a Simple Framework: A decent bank might be worth its Tangible Book Value plus a 25% premium. Adjust this based on your assessment of earnings risk and growth potential.

5. Be Patient: As Stan Druckenmiller said, "The big money is not in the buying and selling, but in the waiting." Sometimes, the best decision is to wait for the right opportunity.

The Role of Reflexivity in Bank Valuation

An often overlooked but crucial concept in bank valuation is reflexivity, popularized by George Soros. In the context of banks, reflexivity suggests a two-way feedback loop between a bank's fundamentals and its market valuation:

- A bank trading at a high multiple might find it easier to raise capital or make accretive acquisitions, potentially improving its fundamentals and justifying an even higher multiple.

- Conversely, a bank trading at a low multiple might struggle to grow or face higher funding costs, potentially leading to deteriorating fundamentals and an even lower multiple.

This reflexive relationship means that market perceptions can become self-fulfilling prophecies to some extent. It underscores why understanding both the intrinsic value of a bank (based on its net income, earnings quality, and growth potential) and market sentiment is crucial for investors.

A lot to think about, but hopefully this helped shed some light on how to value (price) banks.

Remember, as Charlie Munger once said, "It's not supposed to be easy. Anyone who finds it easy is stupid." So embrace the challenge, continue learning, and happy investing!

The best is ahead,

Victaurs

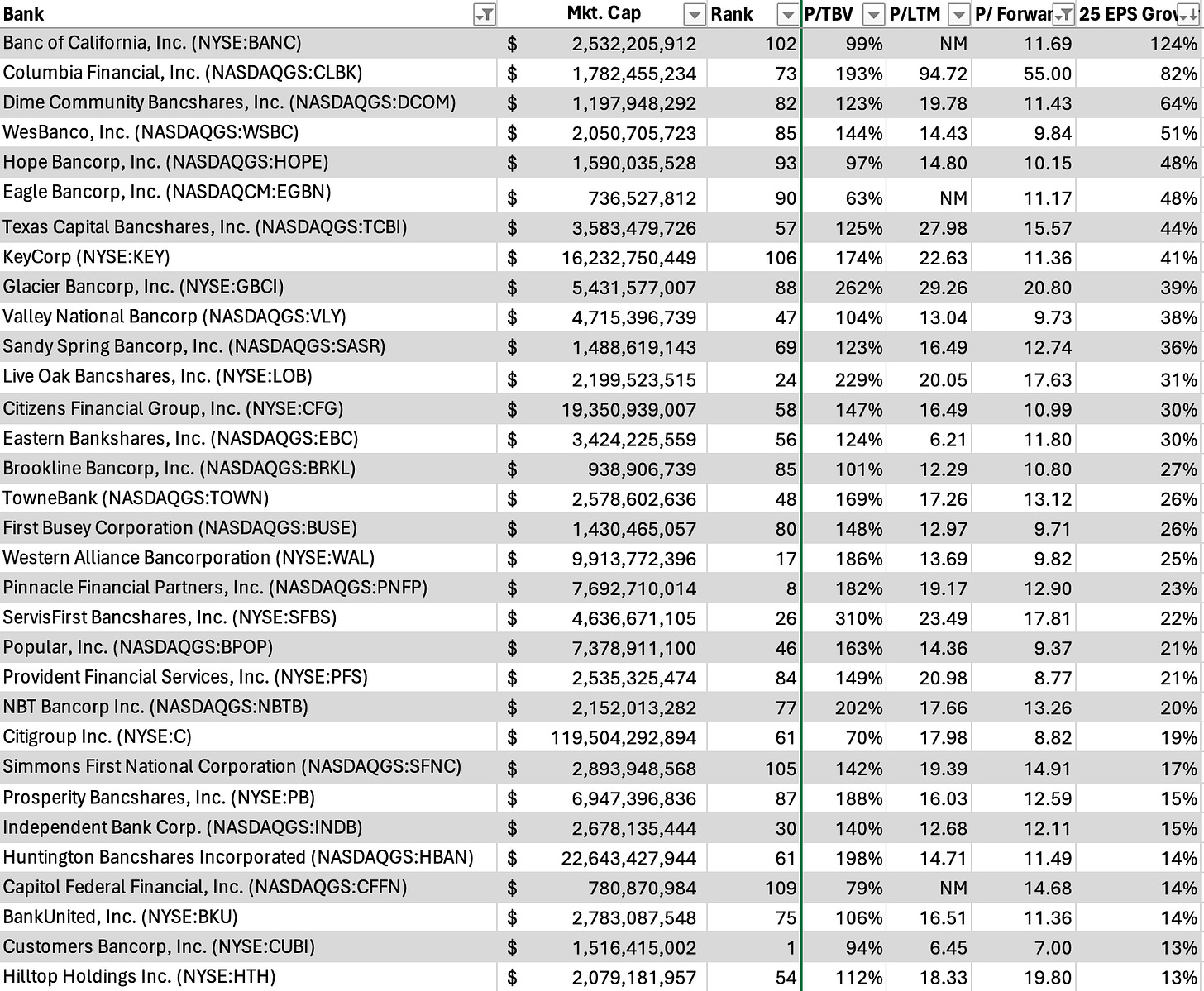

PS - if you made it this far, here’s the richest and cheapest regional & big banks to 2025 ROTCE as well as the banks with the current biggest ‘25 EPS estimates. Normally these are paywalled.