3 Lessons for CEO's Allocating Capital

From an obscure Finnish Banker who mastered the art and the science of growing shareholder value.

What separates thriving institutions from those sold for scraps? It’s not luck—it’s leadership. And in a US banking world coming off some major failures: SIVB, SI, SBNY, and FRC along with some really average longer-term returns, it felt right to share this.

I recently read about Björn Wahlroos in the book Capital Returns: Investing Through the Capital Cycle which provides a masterclass in the art of thinking long-term and growing shareholder value.

Before I get in, the book is a 10/10 read (Capital Returns on Amazon) and I make zero dollars from the link here but wanted to give proper credit where credit was due. Chancellor’s ability to weave historical perspective with economic insight and Marathon’s decades of practical experience in capital allocation make this book a rare gem. It’s not just a guide for investors; it’s the North Star for understanding how industries evolve, how capital flows shape their fortunes, and how to position yourself ahead of the curve.

The central thesis is simple yet profound: capital flows are cyclical. Too much capital chasing an opportunity inevitably leads to poor returns, while a lack of capital in an industry creates fertile ground for outsized profits. The trick isn’t just spotting the cycle—it’s having the discipline to act when others won’t. But as we know, discipline is hard.

That’s why when I think about the state of banking in the U.S. today overall, I see a glaring problem with how capital decisions are made. Some banks in this country are crippled by decisions that cause them to either chase the wrong opportunities, fail to prepare for inevitable downturns, or mis-time leaning into opportunities at the wrong times or wrong prices (hello zombie banks). Misjudged acquisitions, overleveraged bond portfolios, and shortsighted lending practices aren’t just nuisances—they’re existential threats to CEOs and boards. They lead to lower returns, eroded shareholder value, and, in the worst cases, fire-sale exits where once-proud institutions are sold at pennies on the dollar.

What’s the solution? It starts with better decision-making at the top—leaders who understand capital cycles, allocate counter-cyclically, and focus relentlessly on long-term value creation. And I’m not here to say it’s easy, but that it is important.

So here are the three big lessons I learned from Capital Returns from a person I didn’t know existed before reading, Björn Wahlroos, former CEO of Sampo. Wahlroos provides a killer example of how decision making is done. In his tenure, he turned a fragmented, domestically oriented business into a financial powerhouse by mastering the art of capital allocation.

Who Is Björn Wahlroos?

Björn Wahlroos is one of the most influential figures in Nordic finance, renowned for his sharp intellect, counter-cyclical thinking, and mastery of capital allocation. Born in Finland in 1952, Wahlroos started his career in academia, earning a doctorate in economics and working as a professor before transitioning into the corporate world.

In the late 1980s, Wahlroos co-founded Mandatum, a boutique investment bank, where he honed his expertise in financial strategy. In 2001, Mandatum was acquired by Sampo Group, and Wahlroos became its CEO in what was effectively a reverse takeover. Over the next decade, he transformed Sampo from a domestically focused financial services company into a Nordic powerhouse, with dominant positions in property & casualty insurance and retail banking.

Today, Wahlroos is celebrated not only as a business leader but also as an intellectual force in finance. His career is a testament to the power of disciplined decision-making, a deep understanding of capital cycles, and the courage to act decisively in the face of uncertainty.

Lesson #1: Be Leery of the “Hot New Thing”

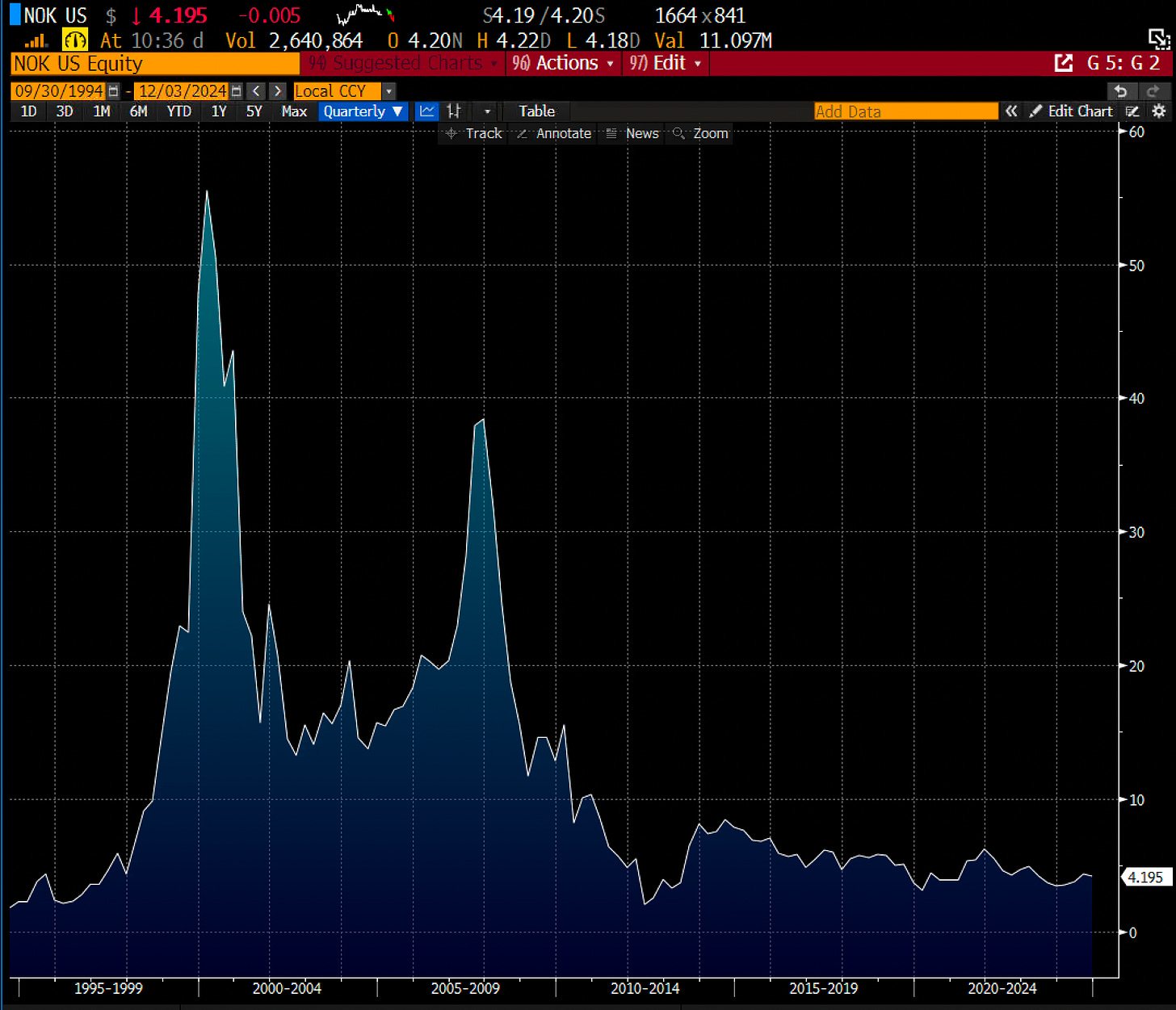

When Björn Wahlroos took over Sampo in 2001, the company owned 1% of Nokia—a stock that represented the pinnacle of high-growth, high-expectation investments at the time. Nokia wasn’t just a company; it was a symbol of Finnish innovation and global tech dominance. It accounted for 22% of Sampo’s net asset value. Most CEOs would have clung to such a prized asset, hoping its star power would rub off on their broader portfolio. What did Wahlroos do? He sold it. Legendary.

By November of that year, he had reduced Sampo's Nokia position from 35 million shares to 6.7 million, locking in an average sale price of €35 per share. At the time, it might have seemed like a controversial move. Nokia was still a leader in its industry, and selling a substantial stake might have been perceived as a lack of confidence. But Wahlroos wasn’t concerned with optics—he was focused on value. Today, Nokia trades at around €7.2 per share, and the wisdom of his decision is glaringly obvious.

The lesson here? Capital allocation isn’t about chasing trends or clinging to narratives—it’s about preserving and growing capital by understanding intrinsic value. In 2001, tech stocks were coming off the euphoric highs of the dot-com bubble. Nokia, despite its dominance, was overvalued in the broader context of its sector. Wahlroos had the foresight to recognize this and the discipline to act. He resisted the emotional urge to hold on to what looked like a sure bet and instead redeployed that capital into more stable, undervalued opportunities.

This decision highlights the importance of looking beyond the surface. Nokia was the hot new thing and was priced for perfection. For investors, this is often a dangerous place to be. When expectations are sky-high, even minor disappointments can lead to massive declines in value. Wahlroos understood that true investing success lies in avoiding those traps and focusing instead on assets that may lack excitement but offer better risk-reward profiles.

Application to US Banking Today

In today’s U.S. banking world, thankfully, most institutions don’t directly own public equities, so the literal lesson of selling Nokia doesn’t apply. However, the principle of disciplined allocation and resisting the allure of hot trends is just as critical when it comes to balance sheet decisions. Whether it’s commercial real estate lending, auto loans, or investing in securities portfolios, the fundamentals remain: hot markets won’t stay hot forever.

It’s easy to get caught up in the momentum of seemingly lucrative opportunities. During a lending boom, volumes soar, spreads compress, and optimism reigns—but this is precisely when risks often build below the surface. Asset prices don’t always rise, cap rates don’t always reflect long-term realities, and cycles always turn. The institutions that chase growth blindly in these moments set themselves up for pain when the music stops.

Even more dangerous is the temptation to dabble in unfamiliar territory. Entering a new market or asset class, especially one that’s suddenly trendy, without a deep understanding of its nuances is a recipe for disaster. For instance, jumping into fintech partnerships, cryptocurrencies, or niche lending categories may seem like a way to capture growth, but without proper due diligence and expertise, these ventures often result in costly missteps.

This all sounds obvious in hindsight, but in practice, it’s where many banks falter. The pressure to chase yields, satisfy shareholders, or follow peers can cloud judgment. Yet the lesson from Wahlroos is clear: sticking to your core competencies, focusing on intrinsic value, and avoiding the seduction of trends is what separates the institutions that thrive from those that fail.

The most successful banks allocate capital with a clear-eyed understanding of long-term risks and rewards, not based on what’s popular today. The discipline to do this consistently is rare—and that’s why it’s so valuable.

Lesson 2: Be Patient and Think Counter-Cyclically

Björn Wahlroos’ transformation of Sampo’s property & casualty (P&C) business into a powerhouse is one of the most compelling examples of strategic patience and counter-cyclical thinking in modern finance. At the time he took over, Sampo's P&C operations were a solid but unremarkable player in the Finnish market, with a 34% domestic market share in an industry nearing maturity. For many leaders, such a position might have signaled the need for incremental improvements or consolidation—but not for Wahlroos. He saw an opportunity to think bigger.

The first move was merging Sampo’s P&C operations into “If,” a pan-Nordic entity, giving the combined business a dominant regional position: 37% market share in Norway, 23% in Sweden, and 5% in Denmark. This consolidation created an oligopoly with substantial pricing power, introducing much-needed discipline to the market. Within just a few years, the combined ratio—a critical profitability measure in insurance—improved dramatically, dropping from 105% in 2002 to 90% by 2005.

But the real brilliance came later. In 2003, Sampo’s partners in “If” ran into financial distress. Wahlroos capitalized on their vulnerability, buying out their entire stake for €2.4 billion. The deal was a classic case of patience meeting preparation: Wahlroos didn’t rush to overpay during the initial merger but instead waited for the right moment to secure full ownership at a favorable price. Today, the P&C business is valued at up to €9 billion—a nearly fourfold increase.

Wahlroos’ mastery of counter-cyclical thinking was on full display again during the 2008 financial crisis. As markets were gripped by panic and asset prices plummeted, Wahlroos had positioned Sampo with just 8% of its portfolio in equities and a large allocation to liquid fixed-income assets. This decision wasn’t luck—it was foresight. Recognizing the vulnerabilities in the market, he reduced risk in the lead-up to the crash, preserving liquidity when it was most valuable.

When the crisis hit, Sampo was ready. Wahlroos deployed €8–€9 billion into commercial credit at fire-sale prices, purchasing bonds from distressed sellers desperate for liquidity. These investments included high-yielding bonds from Finland’s largest paper company, UPM-Kymmene, which generated substantial gains for Sampo—adding €1.5 billion to the company’s bottom line.

Wahlroos’ approach to both the P&C business and the 2008 crisis underscores a timeless truth: opportunities are born in crises, but only for those prepared to act. Success isn’t just about predicting market cycles—it’s about having the discipline to build liquidity during booms and the courage to invest when everyone else is running for the exits.

Application to US Banking Today

In the U.S. banking world today, the lessons from Wahlroos highlight the critical importance of capital discipline, particularly in the realms of M&A and capital raising. For banks, this means holding excess capital—not as a static buffer but as a dynamic resource that shifts with market conditions. The ability to deploy this capital effectively, without overpaying for mediocre M&A deals, requires patience and a long-term mindset. It’s about waiting for the fat pitch—those rare opportunities that offer significant upside without excessive risk.

Far too often, banks engage in “meh” acquisitions driven by fear of being left behind or a desire to appear active to stakeholders. These deals rarely deliver meaningful returns and often lead to regret when better opportunities arise later. The most disciplined institutions, however, know that the best M&A strategy isn’t about doing more deals—it’s about doing the right deals. This involves passing on marginal opportunities, even under shareholder pressure, and preserving dry powder for moments when truly game-changing opportunities appear.

On the capital-raising front, today’s elevated public market valuations offer an excellent opportunity for banks to raise both equity and debt. When markets are strong, the cost of raising capital is lower, and well-timed issuances can significantly enhance a bank’s ability to go on offense when conditions change. The key is to act proactively rather than reactively. Too often, banks wait until capital is scarce or their stock price has declined to raise funds—leading to higher costs and greater shareholder dilution.

Instead, banks should view capital raising as an offensive move, building a war chest when conditions are favorable. This positions them to capitalize on distressed opportunities during downturns, whether through acquiring undervalued competitors, expanding into new markets, or buying high-quality assets at bargain prices. Wahlroos’ approach during the 2008 crisis—having liquidity ready to deploy when everyone else was scrambling—is a perfect example of how preparation and patience can lead to outsized returns.

In essence, the formula is simple but demanding hold excess capital when markets are strong, avoid mediocre M&A deals, and raise funds when the cost is low—not when desperation sets in. Banks that master these principles won’t just survive the next downturn; they’ll thrive in it.

Lesson 3: Avoid Emotional Decisions Like the Plague

In 2007, Björn Wahlroos orchestrated one of Sampo’s most remarkable strategic moves: the sale of its Finnish retail banking operation to Danske Bank for €4.1 billion. At first glance, this decision may have seemed surprising—after all, retail banking was a core part of Sampo’s business. But Wahlroos wasn’t interested in sentimentality or maintaining the status quo. He had a clear, dispassionate understanding of the business’s value and its limitations. Retail banking, with its lower margins and higher operational complexity, offered limited upside compared to what Sampo could achieve by reallocating the capital elsewhere.

The timing of the sale, just before the global financial crisis, was no coincidence. Wahlroos recognized that the market was overvaluing financial assets and that buyers like Danske Bank were willing to pay top dollar. He acted decisively, locking in a premium price while the market was still frothy. It’s easy to see why this move was so critical when you consider what came next: the 2008 financial crisis decimated valuations in the banking sector, leaving less agile competitors scrambling to survive.

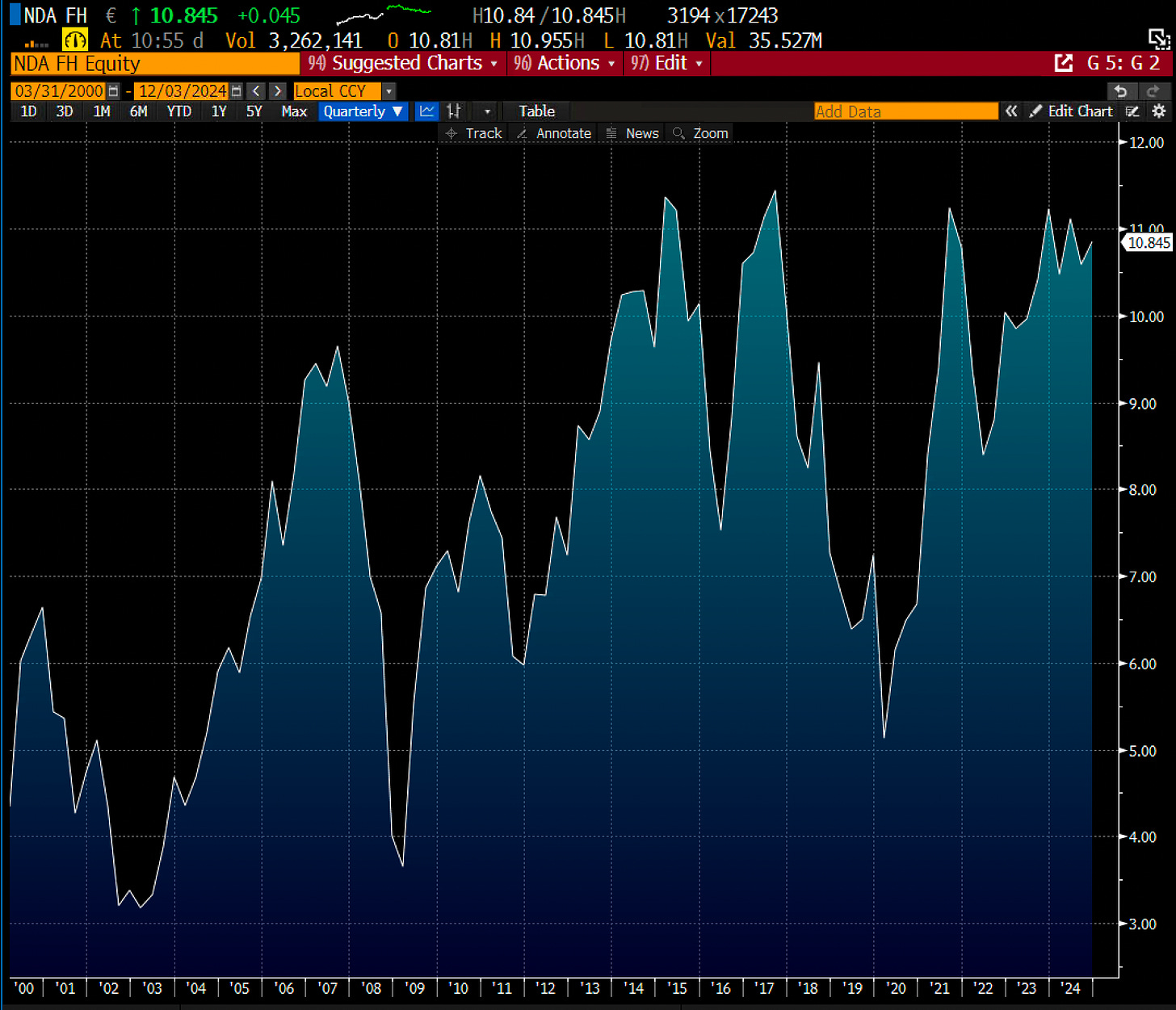

But what makes this decision even more impressive is what Wahlroos did with the proceeds. Instead of sitting on the cash or rushing into risky ventures, he redeployed it thoughtfully. Over time, Sampo built a significant stake in Nordea, the largest Nordic banking group, at an average price of €6.39 per share. This wasn’t just a passive investment—it was a calculated move to gain exposure to a higher-quality banking franchise with a more favorable risk-reward profile. Much of the Nordea position was acquired at a deep discount to book value, around 0.6 times, compared to the 3.6 times book value achieved on the sale of Sampo’s Finnish operations.

This remarkable arbitrage—selling high and buying low—is a testament to Wahlroos’ ability to remain unemotional and focused on value. Today, Nordea trades at €10.85 per share, and Sampo’s stake in the company was a key driver of its growth. Wahlroos’ strategy wasn’t about chasing trends or clinging to legacy assets; it was about maximizing long-term returns through disciplined, fact-based decision-making.

Wahlroos’ approach underscores a critical truth: emotion is the enemy of good decision-making. Whether it’s a business, a stock, or a personal asset, knowing when to walk away is as important—if not more so—than knowing when to double down. Leaders and investors often fall into the trap of holding onto assets out of fear, attachment, or inertia, even when the facts suggest it’s time to move on. Wahlroos avoided this trap by keeping his focus firmly on the numbers and the opportunities ahead.

The key to success isn’t just knowing what to buy—it’s knowing when to sell. Value, not attachment, should drive your decisions. Wahlroos’ ability to sell Sampo’s Finnish retail banking operations at peak valuation and redeploy that capital into Nordea is a masterclass in how to walk away from mediocrity and into opportunity. Whether you’re managing a portfolio or running a business, the lesson is clear: detach from emotion, focus on facts, and always think ahead.

Application to US Banking Today

In U.S. banking right now, this strategy translates into identifying beaten-down asset classes that others are avoiding—not because they lack value, but because fear and uncertainty dominate the narrative. This is where disciplined leaders and teams can excel by focusing on fundamentals rather than optics or market sentiment.

Take office real estate, for example. With hybrid work trends and rising interest rates creating a negative perception, the sector has been under relentless pressure. But not all office properties are created equal. Certain markets or classes of assets—such as well-located properties in cities with robust economic activity or specialized spaces for medical or tech tenants—may still offer strong cash flow potential at deeply discounted prices. A discerning bank with expertise in real estate lending could find exceptional opportunities by carefully underwriting loans in this space, where the rewards justify the risks.

Similarly, mortgage companies are being squeezed by high interest rates and compressed profitability, leading many investors and lenders to steer clear. Yet these companies may represent long-term value plays, particularly for banks that can assess their balance sheets and operational efficiency. For example, institutions with solid servicing portfolios or efficient cost structures might offer an attractive entry point, especially if they’re trading at significant discounts to book value.

The same principle applies to M&A in banking itself. There are plenty of smaller banks or regional players that, at first glance, may seem unappealing due to recent losses or operational struggles. But digging deeper—running the numbers dispassionately and evaluating their core deposit bases, lending franchises, or geographic positioning—can reveal untapped value. Banks that can identify strategic acquisitions during times of sector-wide pessimism often reap the rewards when market conditions improve.

The key to all of this is detachment from emotion and narrative. It’s tempting to follow the crowd, but the best decisions often come from going against it. Whether it’s lending into distressed sectors, acquiring undervalued assets, or pursuing M&A with a long-term view, the numbers must guide the decision—not sentiment, not fear, and not the headlines.

This approach requires patience, expertise, and the willingness to take calculated risks. But history shows that those who can make disciplined decisions during times of uncertainty often emerge as leaders when the dust settles. The opportunity is there for the banks willing to think differently and act boldly.

Closing Thoughts

Björn Wahlroos’ story isn’t just a business case study—it’s a roadmap for how to think, act, and lead in an uncertain world. His lessons remind us of the timeless principles that separate the average from the exceptional: resist the allure of hot trends, prepare relentlessly for downturns, and act with discipline when opportunities arise. Most importantly, they highlight the power of detachment—from emotion, from ego, and from the temptation to conform.

As I reflect on the lessons from Capital Returns and Wahlroos’ career, it’s clear that the problems plaguing many U.S. banks today are rooted in the exact opposite behaviors: chasing fleeting opportunities, failing to build liquidity during booms, and making reactive decisions in moments of stress. These patterns don’t just hurt returns—they destroy institutions.

The antidote is simple in theory but demanding in practice: follow the cycles, focus on long-term value, and act decisively when the time is right. Whether that means selling overvalued assets, raising capital when valuations are high, or buying into unloved sectors at bargain prices, the principles don’t change. What changes is the leader’s willingness to stay disciplined.

Capital allocation isn’t a glamorous topic, but as Wahlroos proves, it’s the single most important lever for building enduring value. The next time you face a decision—whether it’s buying, selling, or waiting—ask yourself this: Am I acting on fact or emotion? Am I following the herd or preparing for the next cycle? And most critically, am I playing the long game or chasing the short-term win? This is so amazingly powerful, so amazingly simple, and yet hard for us all to do.

Because in the end, success in banking—or any business—belongs to those who can master these questions and have the courage to act on the answers. Björn Wahlroos did, and his results speak for themselves. For U.S. banks and their leaders, the blueprint is there. The only question is: will they follow it?

Until next time,

Victaurs

Great overview of a great banking capital allocator. Do you know of any others whose history is worthy of study? Thx.